Third in a series on Civilization

Most of my science fiction stories take place in what I would call “advanced” civilizations. Sci-fi in general considers the impacts of science on people, so that assumes an advanced level of science. This is not generally as true for fantasy stories, which can often be placed in a realm of magic and medieval lifestyles.

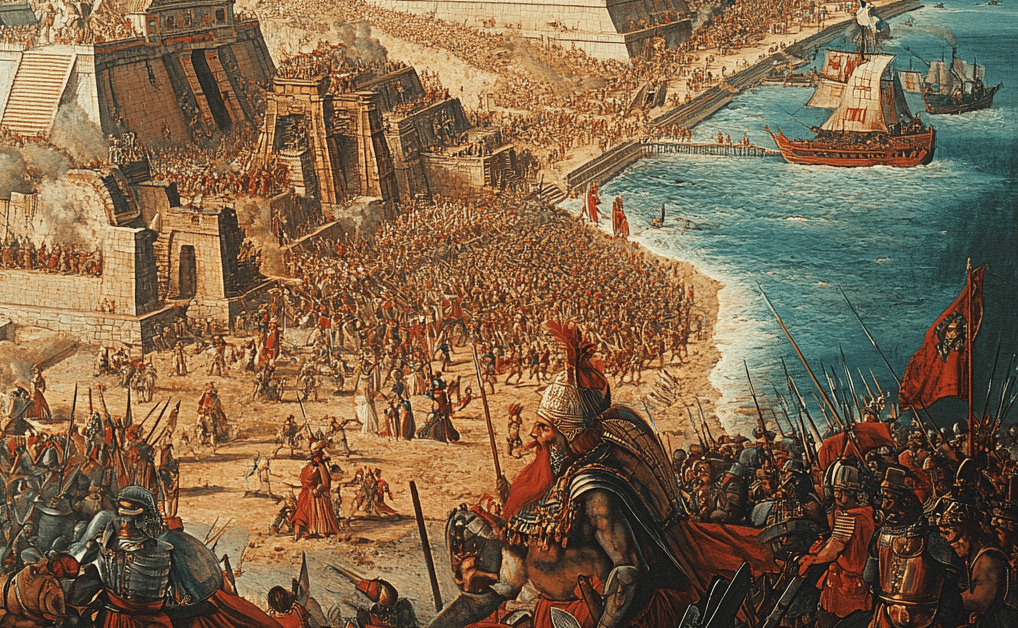

But what is an “advanced” civilization? What makes one more advanced and another more basic? Consider the clash of civilizations that happened when European explorers and settlers arrived in the New World.

Indigenous American populations had many different forms of civilization. The Aztec culture had established agriculture, strong religion, permanent records in stone graphics, and a stratified society. The Muscogee (Creek) culture had strong matrilineal clan systems with a balance between agriculture and hunting, permanent cities with earthwork mounds and satellite towns. The Sioux culture comprised a group of hunting and warrior tribes in nomadic life on the Great Plains, while the Inca Empire achieved monumental stone architectures without the use of the wheel or even a system of writing.

These civilizations were very different from each other. Most were fairly stable in nature, though the Aztec, Inca, and Muscogee cultures had developed significantly in the prior five hundred years. The population of the Americas may have been as much as 70 million.

Against them came the civilization of Europe that had developed over more than three thousand years, starting in Mesopotamia, often called the “cradle of civilization.” The European population at that time was about 90 million in an area five times smaller than the Americas.

Explorers came from several different countries speaking varied languages, but all had developed the technologies to allow populations living in large cities and supporting steel production, advanced weapons, faster transportation, and shipbuilding. They had also weathered and gained some immunity against the diseases incubated in those closely-packed cities.

The history of the next several hundred years shows the reality of such a clash. The European diseases decimated the American population, perhaps by as much as 90%. Follow-on contact showed the indigenous people to be intelligent enough to adopt (and adapt) new weapons and methods from the Europeans, but they could not match the millennia of cultural development of the invaders.

The key difference lies in the concept of civilization: cooperation and specialization by all for common benefit.

Europeans knew how to specialize and offer their individual skills to society. Through cooperation, individuals could learn skills such as metallurgy, advanced agriculture, manufacturing, and societal organization—because other individuals focused on skills that fed and housed the population. The blacksmith need not worry about he and his family starving, so long as his smithing was skilled enough for others to pay him. The successful farmer could obtain a wheeled cart to carry produce to market, where parts of the cart had been manufactured by that blacksmith. Everyone’s life was generally better for the joint cooperation. (Of course, the lives of individuals varied widely; there were definitely “haves” and “have-nots” in the stratified societies.)

Most of the American cultures had not yet learned the same level of cooperation. There was some specialization, often based on gender roles, but not to the same degree as in the European cultures. Life was more egalitarian, with the products of all mostly shared by all—but without deep specialization, it was not possible to develop the variety of specific skills seen in Europe. The Americans could use the weapons they appropriated from Europeans, but they could not create them. Even the skill of writing, of keeping permanent records, was largely absent.

In their arrogance, Europeans understood this difference. They talked of “bringing civilization to the heathens.” They saw the significantly lower standard of living in the Americas, and believed they could upgrade that for the good of the natives. Unfortunately, the cultural clashes went much deeper and the “one-up-one-down” nature of interactions caused mostly resentment and warfare. The native Americans did not understand the benefits they could receive, while the Europeans did not understand the rich cultures they were destroying.

This lack of understanding often comes into play between cultures. My great-grandfather served as a foot soldier in the Confederate Army. Because he was an educated city man in Charleston, we have his first-hand letters from that time.

Ten years after the end of the Civil War, he and his fellow Confederate soldiers were brought to New York and Boston to take part in parades celebrating the re-union of the country. In his writing about that event, he was astonished to realize that the Confederacy had never really had a chance to win after all—because he saw for the first time the kind of industrial base available in the North. Until he saw that, he had never known how much further advanced the Northern civilization was.

Back to my original question: what is an “advanced” civilization? It is one with a greater degree of specialization and cooperation, in which individuals dedicate their lives to unique skills that have value to others. This can only happen, as I noted in my last essay, when the basics of life are provided by the specialization of others.

In my stories, I often hypothesize characters with such specialized skills—such as “flim-flam” Clyde Wandon who runs balloon tours of the upper atmosphere of the planet Bright. Because the stories are placed in advanced societies, I and the reader can assume the life basics also exist. Clyde doesn’t have to plant things to eat; he trades his nefarious skill for money, then trades the money for food.

Just as we do.

Check out the links on DocHonourBooks.com to see my fiction. Sign up for my newsletter to get some informal insight into writing—and an occasional freebie.

Doc Honour

July 2025