Twelfth in a series on the edges of science

The more complex the system, the more difficult it is for science to function well. In earlier posts, I’ve written about how science bases its Truth on the control and repeatability of experiments. If one scientist reports a new theory, proven by his experimentation, other scientists expect to be able to repeat the experiment and get similar results. Confirmation can lead to exploration of causality, trying to understand why these conditions create this result.

In the real world, many systems exhibit what theorists call “emergent behavior,” often a misunderstood topic. (Emergence is not just “the stuff we didn’t expect.”) In its essence, emergent behavior occurs when a system exhibits behaviors that cannot exist at the level of its component parts. As an example, an airplane flies.

The concept of “flight” makes no sense when we talk about the engines, or the fuselage, or even the wings. A wing may be designed to provide lift when moved through the air, but lift is not flight. The emergent behavior of flight only happens when all the parts are assembled in an appropriate manner, then used properly in conjunction with each other.

Emergence exists in both engineered and natural systems. The crystalline shape of snowflakes does not exist at the molecular level. The regular shape of an ant mound happens from each individual ant moving a grain of sand. A widespread Internet crash (as happened this past week) emerges from the unintended shutdown of tens of thousands of computers, and causes the cancellation of thousands of commercial flights.

In each case, scientists can attempt to study the behavior after the fact to theorize cause-and-effect. Sometimes, causality can be determined (as in the CrowdStrike software update); other times, the emergence happens in ways we simply don’t understand (as in the individual wonder of a snowflake).

Often, when the emergent behavior repeats, scientists can study the statistical occurrence to learn when it happens and how to affect it. The entire studies of social science and psychology take this approach. Psychologists study the emergent behavior of human consciousness and reactions, while social scientists study the emergence of collective behaviors. Again, such studies occur after the fact, examining human and social behaviors that have happened.

The problem for science is prediction.

When we know how the component parts interoperate, we can (sometimes) create predictive models with reasonable accuracy. This is the case for the airplane. The theory of flight depends on calculation of lift, weight, thrust, and drag. These parameters can and do make sense at the level of the component parts—even the Wright brothers carefully calculated the weight of the engine they designed. Given detailed measurement and calculation, it is possible to predict accurately the flight characteristics of an airplane. In most conditions, anyway; some behaviors outside the normal envelope can surprise the designers. Not to mention the pilots.

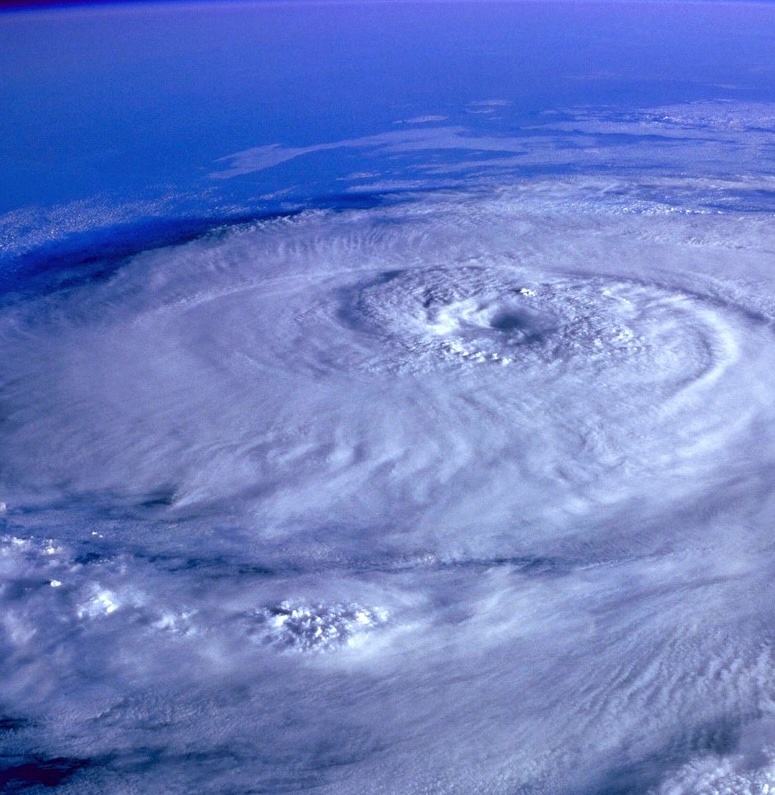

However, we often do not know how the component parts interact. Weather is an emergent behavior dependent on temperature, air movement, heat input, heat absorption, moisture content, and many other factors over both localized and regional conditions. Weather predictions today are astonishingly good, yet equally as astonishingly bad. Plan a day at the beach to learn how inaccurate weather prediction can be. Or watch the predicted tracks of an incoming hurricane, and how those predictions change on an hourly basis.

Emergent behavior is so incredibly difficult for science to work with because we usually do not understand all the interactions. What effect do sun spots have on a hurricane? What does wind shear do to an airplane? How much metal fatigue can a wing sustain? Why does a crowd form, and what grabs its attention? What dust particles contribute to the shape of a snowflake? Scientists have studied each of these with conflicting and confusing results. When factors like these add themselves into the mixing pot that is emergence, literally anything can happen.

Ordinary things of life and reality often rely on emergent behavior. Weather. Traffic. Plant growth. Your computer. Science struggles to predict such behaviors, which are very much at the edges of science.

I write these posts as a way to examine issues that matter to us. In this series on the edges of science, I’ve been trying to shine a light of reality on our often-blind reliance on science. If you find these posts interesting—and by the response, many do—then I also invite you to explore my science fiction. In it, I also explore the edges of science, illuminating areas where “accepted knowledge” might not be as True as we think.

Click on the links here on DocHonourBooks.com to see my fiction. Or join my newsletter to get some informal insight into writing—and an occasional freebie.

Doc Honour

July 2024