Fourth in a series on the edges of science

We say something is complex when we find it difficult to understand. This definition is intuitive, but not very useful in a scientific way. Cambridge Dictionary carries it a bit further, defining complexity as “the state of having many parts and being difficult to understand or find an answer to.” Better, but again not very useful in science.

The field of systems engineering has long been the study of complexity, in which the boundaries of the complex have been moving outward for decades. Systems that were exceedingly complex fifty years ago are routine today, deemed to be “complicated” rather than complex.

This difference is key. An automobile is a complicated system with thousands of interoperating component parts. However, most of the time, the behavior of my car is predictable. It does what I expect it to do, which demonstrates it is not in the realm of complexity.

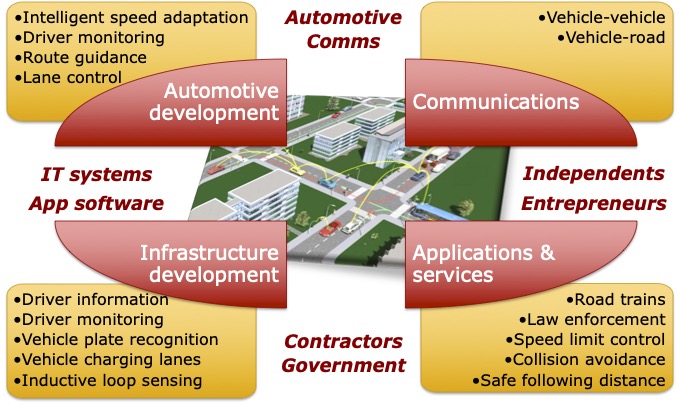

But when I give that automobile self-driving capability and put it in a network of other vehicles, road systems, and communications, sometimes called a “smart highway,” its conduct becomes less benign. There are, of course, cyberattacks that might take over my car. But even without that element of evil, the conflicting commands from different systems frequently create situations in which my car performs unexpectedly. It implements a panic stop for another car that’s only turning off the road. It fails to detect the flatbed truck in front of us. Once in a while, the automated systems actually cause an accident. Most of the time, I have little understanding of what it’s doing. Complexity. But then, neither do the experts. Today, designers are actively working to prevent each new glitch they discover, reflecting only marginally better understanding of the problem than my own.

What does all this have to do with science?

In seeking to understand a phenomenon, scientists isolate an experiment. They remove extraneous factors either during the experiment design or during post-analysis. They reduce the experiment to its essence. They make it repeatable. But only under the tightly-controlled, reduced conditions of the experiment.

They have removed the complexity the real world always offers. They’re operating the laptop without its Internet connection.

The resulting scientific theory is proven by the results. The theory works (approximately, within error bounds) to describe the relationship between a causal factor and its consequences. And the theory continues to work until it encounters a set of pre-conditions and inputs that perturb that relationship. The knowledge of science is often limited to the predictable. In the real world of complexity, that science may or may not work.

Complexity often rears its head in complicated systems made up of many parts, in which the interactions of those parts are recursive with each other and with the environment. Part A interacts with Part B causing a known response (from the science of the parts). The change in Part B causes Parts C and D to respond. The rub comes when the change in Part D also causes a change in the original Part A. This recursion creates a strangely responsive system. With only four parts, this is not usually complex and can be analyzed. But when there are thousands or millions of parts, no amount of modeling and analysis can be enough to understand the possibilities.

Even worse, system analysis often shoves many factors outside the system, calling them “environment.” When analyzing performance of an aircraft, the scientist acknowledges the impact of wind, altitude, air temperature, and humidity—but what if the aircraft itself causes a variation in the air? What if that variation recursively changes the aircraft performance? This is exactly what scientists fought in the “sound barrier” of the 1940s. Many leading scientists of the day thought the sound barrier to be impenetrable, just like we consider the light speed barrier of today.

And beyond that, what if the scientist is completely unaware of that recursion?

In such a case, the scientific analysis presents theoretical performance that is not matched by the complex reality. And the science is then wrong.

Complexity is, by its very nature, a confounding factor in science. The things we don’t understand are the same things we “assume correct” for our science to work.

Doc Honour

September 2023